This suggests that the various ways Indians have developed to use coconuts are ancient, including the practice of scraping their flesh and steeping it in hot water to extract coconut milk. This is an essential ingredient in coastal regions, particularly in fish curries. Many prasadams offered in South Indian temples use coconut milk.

In southern Tamil Nadu a drink called paruthi paal, or cotton milk, is made from steeping cotton seeds (usually with rice) and extracting a similar liquid which is said to have cooling benefits. In Karnataka poppy seeds are treated similarly, often with almonds, to make gasagase haalu, or poppy seed milk. This might be a variant of almond milk, which is common in the Middle East, particularly with Jews, who use it for dishes where, as per kosher rules, dairy can’t be eaten with meat. In an Antique Land, Amitav Ghosh’s exploration of the world of a 12th century Jewish merchant, shows the long interactions of such Jewish traders with Mangalore.

Coconut milk is practically ancient. There are also other local drinks such as cotton milk in Tamil Nadu and poppy seed in Karnataka. The vegan movement has championed sources like soy, oats, almond

This is a response to the rapid growth of plant-based milks. The demand comes from people who are lactose intolerant, or who have concerns about the cruelties inflicted on animals in the dairy industry, or the environmental impact of such large scale livestock raising. The vegan movement has championed milk from soy, oats or yellow peas, sometimes calling them mylk for differentiation hence FSSAI’s specific ban on ‘phonetically similar terms’.

This is also the latest salvo in an old battle, where the dairy industry doubles down on potential competitors. It goes back to the invention of margarine and the furious response from butter producers in the West. They tried everything from bans—which were always struck down by courts— to more vivid ways to persuade people not to buy margarine, like insisting it be coloured an unappetising pink.

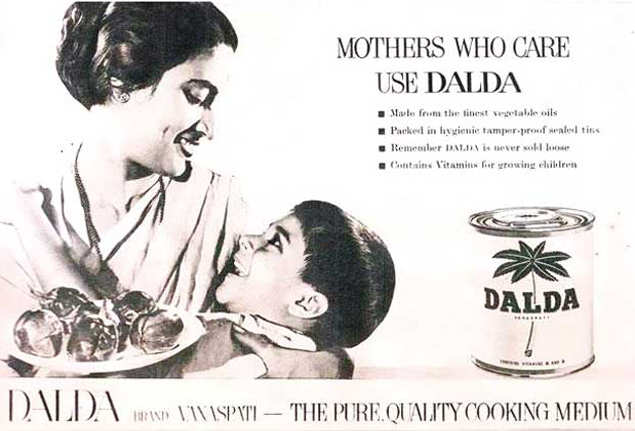

Call for ban on dalda

In the 1950s there was a call for ban on Dalda. Those who wanted the ban called it a false product - one that imitated desi ghee, but was not the real deal. In other words, it was an adulterated form of desi ghee, harmful for health.

Different versions of this battle have been fought in India, for example between ghee and Vanaspati manufacturers in the 1950s, ice-cream and frozen desserts in the 1990s, or more recently over how much butter a ‘butter cookie’ needs to have to be able to use that name. In all these cases the dairy industry claims the high-ground of ‘purity’, with the implication that its opponents are commercially driven promoters of fake products. RS Sodhi, managing director of Amul, took this line when, in an interview with ET, he dismissed objections to the policy from the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) as “based on certain industry lobbies.”

Frozen dessert vs ice cream

In 2017, Hindustan Unilever and Vadilal Group joined forces to take on “Amul” ice cream maker Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) over a television commercial, which allegedly belittled “frozen desserts”. The court asked Amul to take the advertisement off air.

While petitions from parties like FIAPO might benefit plant-based milk producers, they also summarise why many people are turning away from dairy — and being nasty about nomenclature won’t change that. The attempts to ban vanaspati didn’t really work, but what did was addressing the fact that ghee was so scarce and expensive that people opted for the substitute. It was the White Revolution led by Sodhi’s predecessor, Dr Verghese Kurien, that by increasing supply of ghee and bringing down cost, truly undermined the vanaspati market. (Also, manufacturers shifted their focus to less visible markets, like the vegetable fats that go into processed foods).

Even the current wider concern with animal welfare could be met, at least partially, by pointing out that a dairy system like Amul’s which is based on co-operatives of small farmers is more likely to treat cattle better than the impersonal brutality of factory farming. Better practices could also be evolved, with the help of animal welfare experts, for the treatment of cattle on these small farms.

There will still be those who can’t close their eyes to the inherent cruelty involved in dairy farming —like Mahatma Gandhi, who gave up drinking cow’s milk for this reason, and was always guilty about using goat’s milk instead. Forcing these people to keep drinking dairy by denying them alternatives is hardly good marketing, so why not accept there’s no harm in them finding substitutes that still, in a backhanded compliment to dairy, feel the need to use similar names?

And smartest of all might be to cooperate rather than compete, with dairy companies using their considerable expertise to make products from plant-based fats and liquids like coconut milk, which have roots as deep as dairy in India.

September 01, 2020 at 02:58PM

https://ift.tt/2YSqM2I

Can't call it milk, but does it change anything? - Times of India

https://ift.tt/2XiyktG

Milk

No comments:

Post a Comment