A 90-year-old patriarch, his jilted heirs, and the public implosion of the South Shore’s stealthiest wealthiest clan.

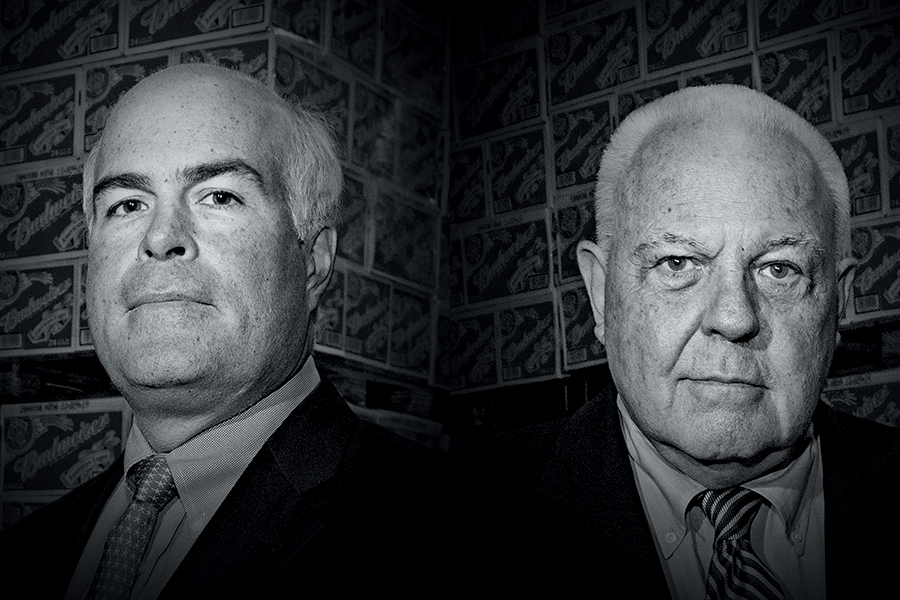

Tim Sheehan and his brother John are suing their parents, Jerry and Maureen, over the way Jerry has managed the family business. / Photo by Leo Gozbekian

There is a mysterious building along Route 3 in Kingston that just about everyone in Boston has seen when driving home from the Cape but practically no one knows anything about. The nondescript name plastered on the front of the massive structure, L. Knife & Son, certainly doesn’t give anything away, nor do the windows that are tinted so dark it’s impossible to see inside. The only hint of what goes on in there are the beer trucks lined up outside and a red Budweiser sign on the façade. In fact, until recently at least, most people had no idea that the building is home to one of the most successful beer distributors in the nation, nor that it has made the Sheehan family, who own and run it, some of the most fabulously wealthy people in the state.

None of this is by accident. The Sheehans give new meaning to the term “stealthy wealthy.” They have studiously remained under the radar, out of the newspapers, and missing in action on the charity gala circuit, even as the family quietly funnels untold millions into charity. Not even Jack Connors, Boston’s longtime philanthropist extraordinaire, had any idea who Jerry Sheehan, the family patriarch, was until about a decade ago. “I had driven by his distributorship a thousand times, saw the sign that said, ‘L. Knife & Son,’ but until the day that I was introduced to him at a reception for his alma mater, the College of the Holy Cross, I had no idea who he was,” says Connors, who has since gone on to become a close friend, business adviser, and partner in philanthropy with Jerry.

The Sheehans, though, are no longer under the radar. Earlier this year the family and their business exploded into Boston’s consciousness—and in the worst way possible. They did not become known for the remarkable story of how they built a billion-dollar business from what was once an immigrant’s humble grocery pushcart, nor were they recognized for their philanthropic largess. Plastered across the front page of the Boston Globe, above the fold no less, was an article detailing a bitter family feud as described in a lengthy lawsuit filed by two of Jerry’s sons—Tim, who had long been poised to take over the family business, and John—against their octogenarian parents.

The lawsuit alleges that the parents were paying themselves exorbitant salaries and living a lavish lifestyle at the expense of the profits owed to the three sons who have taken an active role in the family business. It also alleges that Jerry was siphoning off profits that should have gone to the active sons to distribute them equally among the couple’s eight children, including the five who don’t work for the family company. This, Tim and John say, was part of a concerted effort by Jerry and their mother, Maureen, to level the stacks among the siblings. They also accuse the parents of making an end run around the family foundation to donate money to other charities—all at the expense of the health of the family companies.

The Globe article, which also included a statement from Jerry’s representatives calling his sons ungrateful, was picked up by media around the world, causing much pain for the famously low-profile family patriarch, Connors says. But the buzz it generated was to be expected, explains Ted Clark, executive director of the Northeastern University Center for Family Business. “When family businesses work well, nothing beats them,” he says. “This obviously at one point worked super well. But now with the bickering and fighting, you can’t look away. It’s like a car accident.”

Even as the news of the lawsuit pulled back the veil on the enigmatic building on the side of Route 3 and the people who built the business inside, the accusations have raised far more questions than they have answered. Chief among them: How did such a private and successful family implode in such a spectacularly bad way?

As a teenager Tim loaded beer trucks; he went on to succeed his father as CEO of the family company. / Photo by Leo Gozbekian

About a century before it turned into an internecine nightmare, the story behind L. Knife & Son was the quintessential American dream. When Maureen’s grandfather Luigi Cortelli, a shepherd from Italy, was 16 years old in 1898, he boarded a steamship to America, settling in an Italian community in North Plymouth, where he made a living selling peanuts on the street. Eventually, he saved enough for a grocery pushcart and then bought a store. Keen on continuing to expand his business and unable to secure a bank loan because of his Italian name, he started calling himself Louis Knife—the English translation of his name—for business purposes.

When his son, Domero—the “son” in L. Knife & Son—finished eighth grade, he quit school and joined the family business. It was Domero who in 1934 made a risky business deal that would change the family fortunes for generations to come: He and his wife, Sylvia, signed on to become the distributors of a beer brand that was, at the time, not very well known on the East Coast: Anheuser-Busch.

The third generation of the company was set into motion when Domero’s daughter, Maureen Cortelli, attended a tea dance at Newton College of the Sacred Heart, where she was studying. In walked a tall man with broad shoulders, a powerful build, and a deep, gravelly voice who hailed from an Irish family in New Jersey and was studying at Holy Cross in Worcester. She and Jerry fell in love and were married in 1955, while he was a year into his two-year stint as a lieutenant in the Marines stationed at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. The next year, after the birth of their first child, Margaret, they moved to Plymouth, and Jerry went to work as a route salesman for L. Knife & Son at a time when the company had only 14 employees.

The couple quickly grew their family, having eight children in the span of nine years. They raised them in a five-bedroom home with a gambrel roof on a slight rise off Route 3A. It was not very large—even smaller given the fact that the Sheehans often hosted exchange students. It wasn’t particularly fancy, either, but if the family looked straight across the road down their neighbors’ driveway, they had a clear view of the green water of the bay and the impossibly narrow spit of sand that juts into it.

Every neighborhood has that one house that becomes the center of gravity for the children in its radius. On Warren Avenue in Plymouth, that house was the Sheehans’. Not only was the home bursting at the seams from the couple’s own eight children and exchange students, but it was also often overrun with neighborhood children. “It was a lot of fun all the time,” says Peter Gilmore, who grew up across the street and is a lifelong friend of Tim’s. “They were very accepting of the children in the neighborhood. People felt very welcome there. There was an open door.” In the summer, Maureen would regularly load all of her children and the neighborhood kids into her Land Rover and drive them to the beach; when they arrived, they would pour out onto the sand as if it were a clown car. Somehow there was always room in the car for the picnic lunch she would lay out for them all.

Jerry and Maureen’s family wasn’t the only thing that grew rapidly once they arrived in Plymouth. Jerry went out every day on sales calls—10,000 in the first seven years, by his own estimate—constantly pushing to expand the company’s clientele. Meanwhile, he urged Maureen’s father to grow the business by branching out into other beers, but Cortelli resisted. He was content, Jerry has said, with what he already had—enough money and the luxury of time to spend with his family.

It wasn’t until Cortelli unexpectedly passed away in 1963 that Jerry got the chance to pursue his vision of growth. He bought out his mother-in-law and sister-in-law and took over as president. Over the years, he built an empire and amassed great wealth. In order to protect this fortune for his children and the children they would one day have, in 1969 Jerry and Maureen put all of their shares of the family company into eight trusts. This meant all of the company’s profits would be distributed among the children and not go to their parents.

As he found extraordinary success, Jerry could have afforded a bigger home or even a more elegant one. But, Gilmore says, that was simply not his style. The Sheehans were devoid of pretensions, extraordinarily down-to-earth, and exceedingly generous. As Jerry became a significant philanthropist, he was adamant that he didn’t want buildings named after him or fanfare around his gifts. “He has a sort of natural humility that I find winsome,” says Cardinal Seán Patrick O’Malley, who got to know Jerry through his support of Catholic schools. “He cares about people, particularly those in need. I just find him a wonderful human being.” People who know Jerry and Maureen say that what mattered to the couple wasn’t their image. It was family.

There was never one clear heir apparent among the Sheehan siblings who was preordained to succeed Jerry in running the business. Still, it seemed obvious that Tim would go on to work for his father.

There was never one clear heir apparent among the Sheehan siblings who was preordained to succeed Jerry in running the business. Still, it seemed obvious that Tim would go on to work for his father. In fact, by the time Tim was in middle school, he already was.

Every summer morning at 3:15 a.m., when the air was still cool and the sun had not yet risen over the bay, 14-year-old Tim would ride his bike down the driveway and onto 3A and continue north up the coast, in the dark, for 45 minutes until he arrived at L. Knife to load beer trucks. His responsibilities only grew from there. “I think his father worked very hard at introducing Tim to how to be a good businessman,” Gilmore says. “He was always in tutorials; he was always being trained.”

After graduating from his father’s alma matter, Holy Cross, however, Tim decided to strike out on his own, taking a job as a corporate analyst at Anheuser-Busch. He rented an inexpensive apartment in a rundown part of St. Louis that he shared with a few roommates, drove a beater of a car, and told no one that he was the heir to a large beer distributorship. “I interacted with a lot of sons and daughters of Anheuser-Busch wholesalers over the years,” says Mark Lamping, a colleague at the time who went on to become close friends with Tim, and who currently serves as president of the Jacksonville Jaguars. “There was a fair share of them that came across as very entitled and spoiled, and Tim was the antithesis of that.”

Tim did well at Anheuser-Busch, Lamping says, winning over his superiors with his ability to compromise and resolve conflicts between the company and wholesalers. There was no doubt he could have gone far there. Instead, he returned to the family fold. While in St. Louis, Tim uncovered an opportunity to acquire a struggling Anheuser-Busch wholesaler near Syracuse, New York, and brought the idea to his family. There are strict rules for acquiring an Anheuser-Busch wholesaler—known as becoming an equity agreement manager—beyond one’s demonstrated business experience. “Someone from the Sheehan family had to invest their own money into the business. And that person had to move to Syracuse to run the business. I agreed to do all of those things,” Tim told me. “I was only 26 years old at the time. And I had to use my entire life savings and take out a personal loan of $50,000 to buy my share of equity in the distributorship. I also had to guarantee the distributorship’s financial obligations of nearly $2 million.”

After moving to Syracuse with his wife, Christy, whom he met in St. Louis, Tim says he often worked seven days a week, not just running the business but also loading and driving trucks. Within a year, a wholesaler that had lost a million dollars the year before was now turning a profit.

Then Tim’s younger brother John, who by then was working at Anheuser-Busch, uncovered an opportunity to acquire another struggling wholesaler, this one in Wisconsin. Anheuser-Busch demanded that Tim relocate to be the equity agreement manager there as a condition of the sale, and Jerry urged him to do so and let John take over the position in Syracuse. But by then Tim had a family he was reluctant to uproot—and he didn’t like the idea of losing the equity he’d poured into the Syracuse wholesaler. So Jerry came up with a solution.

In 1984, he established a second series of trusts to divide up the profits from all of the new wholesalers the company was acquiring. According to Tim, the trusts of the three sons who worked in the family business—known as the Sheehan Family Companies—would have the opportunity to acquire 60 percent of any new wholesalers the Sheehans bought, and reap 60 percent of their profits. The remaining 40 percent, meanwhile, would be owned equally by all eight siblings. The original companies, including L. Knife and Seaboard Products, a Danvers-based wholesaler servicing the North Shore, would continue to be owned in equal shares by the trusts of all eight siblings. With this agreement in hand, Tim felt comfortable moving his family to Wisconsin. The Sheehan business, once a local powerhouse, was on its way to becoming a national success.

In 1993, Tim said he “was summoned” back to Massachusetts to take over as the equity agreement manager of Seaboard in Danvers. For the first time since he was a kid, he was living in Massachusetts and working side by side with his father. In 2000, Tim took over as equity agreement manager for L. Knife after, he alleges in his lawsuit against his parents, Anheuser-Busch demanded Jerry step down. According to someone familiar with Jerry, however, Anheuser-Busch did no such thing and Jerry has always had very good relations with the company and the Busch family.

The winds of succession continued to pick up speed. In 2003, the company established a board of advisers—composed of one active sibling, one inactive sibling, and four independent members—that began working to identify and groom a potential successor to Jerry, who was already in his seventies. Ultimately the board identified Tim as that person, and he was gradually promoted to roles of increasing power within the business.

In many ways, the man who would succeed Jerry was an awful lot like him: hardworking, down-to-earth, and driven by excellence. “They’re both the same. They want to run the best company,” says Bill Seckinger, the owner of Muckey’s Liquors and an L. Knife customer who considers himself a good friend of both Tim’s and Jerry’s and says both are exceedingly nice people.

In other ways, though, some of Tim’s friends say he was cut from a different cloth. One friend says that in contrast to Tim’s affability and diplomatic leadership skills, Jerry “comes off like a Marine drill sergeant.” Another says, “You respect Jerry but you like Tim, which isn’t to say you don’t respect Tim, too.”

Many people who know him describe Jerry as an old-school businessman. The first time Dann Paquette, owner of the now-defunct Pretty Things Beer & Ale Project in Somerville, drove down to Kingston to meet with Jerry to hammer out a contract for the distribution of his beer, he was led into a dimly lit room, where he found Jerry seated at the far end of a very long wooden table with a beer—Paquette’s beer—in his hand and a cigar in his mouth. “It was like looking into the past,” Paquette told me. “It just felt like an old-fashioned, hard-working, deal-making, beer-selling world.”

The future, though, was not too far behind. In 2008, Tim took over from his father as CEO of L. Knife, representing the third generational transition of power for the company. Jerry didn’t go far, though, keeping the title of chairman and staying involved in the day-to-day operations. More important, because he controls all of the voting shares in the Sheehan Family Companies, he retains ultimate power.

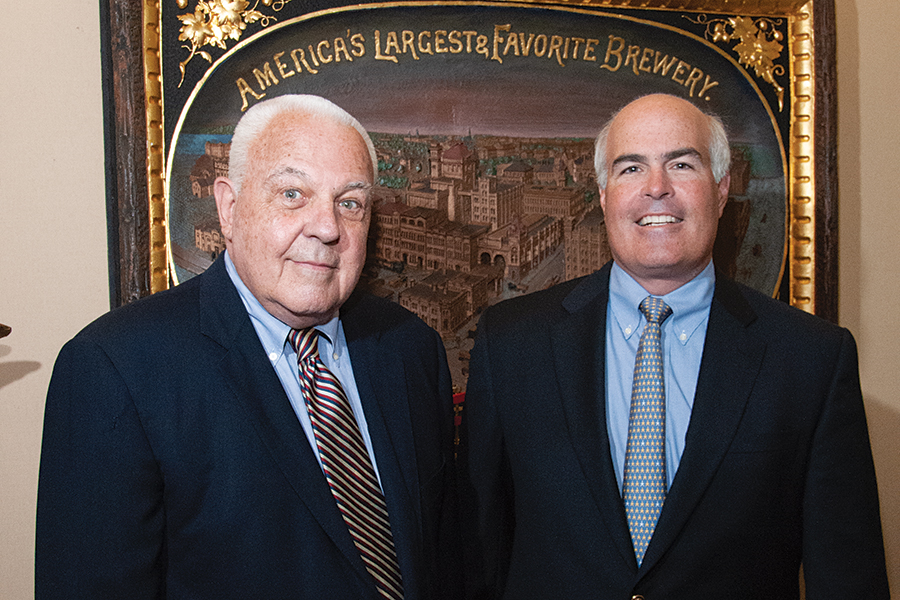

Still, the news seemed to herald a momentous shift at what by then was one of the nation’s most successful wholesalers, and made the cover of Beverage World magazine. In the cover photo, Tim and his father wear identical dark jackets and blue dress shirts while standing together against a backdrop of beer kegs. Tim is smiling, relaxed, his elbow resting on a barrel. Jerry, by contrast, is standing with his hands at his side with what seems to be a lost look on his face.

People who know the Sheehans say in many ways Tim and Jerry are very much alike: lacking in pretension, hard-working, and always striving to run the best company. / Photo by Leo Gozbekian

Well before the lawsuit or the troubles that preceded it, there were subtle hints that all was not well between father and son. “I always knew there was some kind of strain there with Tim and Jerry,” Bill Seckinger notes. “You always felt there was some little thing there. I always wondered, but I never asked, but you get that feeling, you know?” Seckinger says he thinks the tension had to do with something he understands all too well from running a business with his own son. “Like my son, I think Tim wanted to run the business,” he says. And like Jerry, Seckinger says, he has a hard time stepping back from running it himself.

Meanwhile, Jack Connors, who became friendly with Jerry over the past decade, says that Jerry doesn’t talk a lot about his sons. “He’s often spoken about his daughters. And I’ve met two of his daughters,” he says. “But I got the sense that he wasn’t that close to the sons.” One person who knows Jerry said he felt that Jerry was disappointed in his sons and thought they had a sense of entitlement, having been born into the business.

From the perspective of people who know Tim, Jerry was tough on his eldest son. “Jerry basically wants things his way always. He is a powerful patriarch. A former Marine, he was most comfortable giving orders and having people follow them exactly,” a friend of Tim’s says. “Tim has had to play the role of number two and toe the line.” The friend also says it seemed like father and son had very different ways of doing business. “Tim’s whole approach to everything is like that Tip O’Neill saying that all politics is local. To Tim, all business is local. He gets to know people. He is a great listener,” the friend explains. “The old way of doing business was very hard-nosed, and I think Jerry was very dedicated toward growth and very private.”

Renowned beer importer Dan Shelton found out just how cutthroat Jerry could be when he tried to get out of his famously iron-clad distributorship agreements. One of the two times he sued the Sheehans to get out of a contract, he ultimately agreed to settle for a sum that he says was considerable to him but left him wondering, “What is Jerry Sheehan going to do with $10,000? It was almost like Jerry was saying, ‘We are going to let you go, but we are going to make sure you know it is on our terms.’” (Regardless, Shelton says he remains very fond of Jerry.)

Some aspects of Jerry’s way of doing business didn’t sit well with Tim. In a memorandum to the board in 2011, he said he was getting “daily” feedback from employees, business partners, and their employees about Jerry’s “impatience, arrogance and disrespect for others.” It’s a charge a person with knowledge of the situation says is simply not true, adding that there isn’t high turnover among company employees, many of whom have worked there for decades.

A year after Tim sent that memorandum, the board decided Jerry should step back from the day-to-day decision-making at the Sheehan Family Companies and that Tim should become head of the company. The fallout was swift. “My father reacted by demoting me from the position of CEO of the Sheehan Family Companies,” to equity agreement manager of L. Knife, Tim told me. “He also disbanded the board of directors after they criticized him for demoting me.”

The war between father and son didn’t stop there. In 2015, the state’s Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission charged the Sheehan-owned Craft Brewers Guild with alleged wrongdoing for offering cash payments to Boston bars and retailers—approximately $120,000 in kickbacks over the course of the previous five years—in exchange for giving the craft beers they distributed favorable tap placement, which is illegal. The commission slapped the Sheehans with a $2.6 million fine, the largest it had ever levied. While those in the beer industry say the pay-to-play scheme is actually quite common among distributors, the family patriarch was not having it. Jerry, who is “squeaky clean, just very honest…was appalled,” says someone who knows him. According to that person, Jerry thought Tim was the one responsible for the company engaging in these pay-to-play transactions. Tim strenuously denies this claim. “I have never heard that Jerry holds me responsible for the Craft Brewers Guild violation,” he says, “and I can’t think of any reason he would, because I did not control Craft Brewers Guild and was not involved in it. During my 40-plus years in the alcohol beverage business, I have never committed a violation of any kind.”

Differing management styles weren’t the only thing causing strife within the company. Tim and his brother John, who runs the Wisconsin wholesaler, were also growing concerned about what they allege was a pattern of draining resources from the so-called 60/40 companies—the ones in which they and a third active sibling, Chris, had the greatest amount of equity—to divert the funds to the companies owned equally by the active and non-active siblings. This, they claim, was part of Jerry and Maureen’s concerted effort to level the stacks among their eight children.

What’s more, Tim and John allege, their father and mother took exorbitant salaries to fund an increasingly lavish lifestyle that included expensive jewelry, art, and antiques, much of which is housed in their palatial home in Duxbury where they moved after their children were grown, as well as a $1.3 million stone wall around the family’s farm in Plympton that took craftsmen many years to build.

In the lawsuit, Tim and his brother also took issue with Jerry and Maureen’s philanthropic giving beyond the family foundation, which Jerry and Maureen established in 1993 with the mission of conserving land and water in the southeastern part of the state and supporting early-childhood education in Brockton. The sons allege that Jerry has used corporate funds to make exorbitant contributions to his and Maureen’s “pet charities,” like funding scholarships at Holy Cross and donating $25 million to Jerry’s high school, St. Peter’s Prep (where he is the largest donor), primarily for scholarships. From a public relations standpoint, that might just be among the most unfortunate turns of phrase ever used—after all, it seems rather heartless to begrudge philanthropy. Still, the brothers allege this was done at the expense of the companies and their employees.

Tim raised all of these issues with his father, and in late 2017 agreed to initiate mediation in hopes of resolving them. Jerry apparently didn’t take it well, Tim says. Soon after, he fired Tim from the company after 30 years of working together. “It wasn’t even a face-to-face conversation. I received a one-page letter,” Tim says. “Obviously, that was incredibly frustrating given that building the Sheehan Family Companies has been my life’s work.”

Jerry has a different interpretation of the events that led up to Tim’s firing. “Suffice it to say that the issues the company had with Tim were very serious and warranted serious action,” says someone with knowledge of the situation, while declining to elaborate. John, meanwhile, still works for the family company. Meanwhile, Jerry and Maureen’s representatives said in a statement that Tim and John have long been opposed to Jerry’s efforts to advance the “core Sheehan family values of generosity to employees and philanthropy.”

While he was in the heat of battle with Tim, Jerry penned a letter to his grandchildren on behalf of himself and Maureen to tell them their hopes for how they will handle their inherited wealth. “There is a saying, ‘With great privilege comes great responsibility.’ We hope you will live your life and use your inherited wealth in a manner that reflects our core values: humility, respect, hard work, and generosity toward others,” it said, reminding them that they were all in the one percent economically.

The letter recounted the family history and the incredible growth of the business—which in 1973 had just two Massachusetts distributors (L. Knife and Seaboard) and today has 20 across the nation and is valued at $1.5 billion. In many ways, the letter reads like a response to the complaints that Tim and John had made about the way Jerry was managing the companies and a platform for Jerry to take credit for the growth and success of the business, which his sons believe is largely theirs. While the letter obliquely mentions in passing the contributions of “some of our children who got involved in the business,” it barely refers to Tim, John, or Chris.

After attempts to mediate over the course of three years ultimately failed, Tim and John made the decision to sue their parents. (Their oldest sister, Margaret, in her capacity as a director of the company, was also named as a defendant.) “It’s sad to say that I’ve come to feel that the person I thought I should be able to trust the most, my father, has turned out to be the person I could trust the least,” Tim told me, choking up. “This was certainly not part of the American dream that my grandparents had when they started the company over a century ago.”

The day after Christmas last year, Jerry and Maureen were alone at their home in Duxbury when a stranger drove down their long driveway, got out of the car, and rang the bell of their sprawling seaside mansion where, across a patch of tidal marsh, they enjoy an unobstructed view of Duxbury Bay. When they answered the door, they were served with the lawsuit.

Family observers detected a certain Scrooge factor involved in the timing of the lawsuit. “After the last attempt at mediation failed, there was no crisis or expiring of the statute of limitations or reason to file a lawsuit immediately, and certainly not to serve it the day after Christmas,” a person with knowledge of the situation said. “There was no reason whatsoever to do that, but they did. Merry Christmas, Jerry and Maureen.”

About a week later, news of the lawsuit made its way to the Globe, and the story was soon picked up across the country and abroad. It may have been the first time most people had heard of the Sheehans, but it sent shock waves through the beer community in Mass-achusetts, and among the employees and customers of the company.

Apparently, no one at headquarters is talking about the suit, or the allegations within it. “Everything is hush-hush,” says Seckinger, adding that no one knows anything more than what’s been reported. Meanwhile, the only public comments Jerry’s representatives have made were in a statement that was quoted, in part, in the Globe story. It says that because the only compensation Jerry receives is his salary, which he donates entirely to charity, he does “not benefit personally from any of the business decisions described—often inaccurately—in the suit.” The statement also took his sons to task for being so ungrateful after having led a life of “unparalleled privilege,” noting that thanks to Jerry’s largess, each son has a net worth “well in excess of $100 million.” Jerry and Maureen’s lawyers have filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Tim, for his part, was upset by his father’s statement. “He used it to take pot shots at me and my brothers personally rather than to address the allegations in the lawsuit head-on,” he told me. “The lawsuit against my father is purely a business dispute, not a personal one…. It is just a last resort to get my father to live up to his legal obligations.” Tim disagreed with Jerry’s characterization that everything Tim and his brother have is thanks to their father’s largess and that they simply want more, the latter of which at least some people at L. Knife also believe. “This case is not about greed. It’s about ethics, and integrity, and fiduciary obligations to shareholders. Besides, we’re not the ones who have drained millions and millions of dollars from a company for personal benefit,” Tim said, adding that what he and his brothers have comes from decades of hard work and sacrifice.

Meanwhile, Cardinal O’Malley says he hopes for a reconciliation among the family members. “All of us understand what dysfunction is in families and how difficult it is at times to forgive each other and help each other,” he says. “I pray for them.”

In February, Jerry turned 90. Despite his age and the pandemic, he still goes to the office, like he always has, six days a week. People who know him say he continues to pore over documents and is up on the details of the business.

When Seckinger and his wife last met with him, Seckinger says she asked Jerry when he was going to quit. Seckinger says Jerry used to tower over him, looking down at him when they spoke, but that day, because he is a little stooped now, he looked up at them to answer. “I don’t know what else to do,” he said. “This is what I do.”

June 16, 2021 at 02:09AM

https://ift.tt/3pVJMcI

Inside the Fight over a Billion-Dollar South Shore Beer Empire - Boston magazine

https://ift.tt/2NyjRFM

Beer

No comments:

Post a Comment